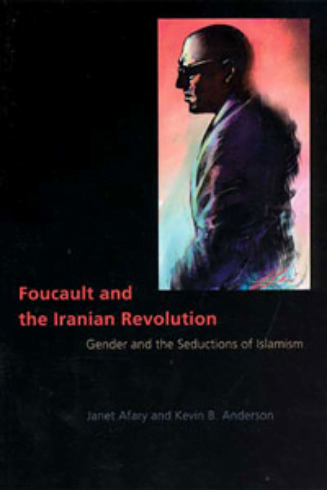

Foucault and the Iranian Revolution

Publisher: University Of Chicago Press

Date: June 20, 2005

ISBN-10: 0226007863

ISBN-13: 978-0226007861

Translations:

This study illuminates Foucault’s support of the Islamist movement and how his experiences in Iran contributed to a turning point in his thought, influencing his ideas on the Enlightenment, homosexuality, and his search for political spirituality. Co-authored with Kevin B. Anderson. In 1978, as the protests against the Shah of Iran reached their zenith, philosopher Michel Foucault was working as a special correspondent for Corriere della Sera and le Nouvel Observateur. During his little-known stint as a journalist, Foucault traveled to Iran, met with leaders like Ayatollah Khomeini, and wrote a series of articles on the revolution. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution is the first book-length analysis of these essays on Iran, the majority of which have never before appeared in English. Accompanying the analysis are annotated translations of the Iran writings in their entirety and the at times blistering responses from such contemporaneous critics as Middle East scholar Maxime Rodinson as well as comments on the revolution by feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. In this important and controversial account, Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson illuminate Foucault’s support of the Islamist movement. They also show how Foucault’s experiences in Iran contributed to a turning point in his thought, influencing his ideas on the Enlightenment, homosexuality, and his search for political spirituality. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution informs current discussion on the divisions that have reemerged among Western intellectuals over the response to radical Islamism after September 11. Foucault’s provocative writings are thus essential for understanding the history and the future of the West’s relationship with Iran and, more generally, to political Islam. In their examination of these journalistic pieces, Afary and Anderson offer a surprising glimpse into the mind of a celebrated thinker. Introduction Part I Foucault’s Discourse: On Pinnacles and Pitfalls 1. The Paradoxical World of Foucault: The Modern and the Traditional Social Orders 2. Processions, Passion Plays, and Rites of Penance: Foucault, Shi’ism, and Early Christian Rituals Part II Foucault’s Writings on the Iranian Revolution and After 3. The Visits to Iran and the Controversies with “Atoussa H.” and Maxime Rodinson 4. Debating the Outcome of the Revolution, Especially on Women’s Rights 5. Foucault, Gender, and Male Homosexualities in Mediterranean and Muslim Societies Epilogue: From the Iranian Revolution to September 11, 2001 Appendix: Foucault and His Critics, an Annotated Translation

~~~~~~~~~

From the Introduction

Throughout his life, Michel Foucault’s concept of authenticity meant looking at situations where people lived dangerously and flirted with death, the site where creativity originated. In the tradition of Friedrich Nietzsche and Georges Bataille, Foucault had embraced the artist who pushed the limits of rationality and he wrote with great passion in defense of irrationalities that broke new boundaries. In 1978, Foucault found such transgressive powers in the revolutionary figure of Ayatollah Khomeini and the millions who risked death as they followed him in the course of the Revolution. He knew that such “limit” experiences could lead to new forms of creativity and he passionately threw in his support. This was Foucault’s only first-hand experience of revolution and it led to his most extensive set of writings on a non-Western society. Foucault first visited Iran in September 1978 and then met with Khomeini at his exile residence outside Paris in October. Foucault traveled to Iran for a second visit in November, when the revolutionary movement against the shah was reaching its zenith. During these two trips, Foucault was commissioned as a special correspondent of the leading Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, with his articles appearing on page one of that paper. Foucault’s interest in the Iranian Revolution was much more than a journalistic curiosity. His earlier work had shown a consistent though subtle affinity for the Orient and the more traditional social norms of the East, as well as a messianic preoccupation with Eastern thought. Foucault believed that the demise of colonialism by the 1960s had brought Western thought to a turning point and to a crisis. During a 1978 encounter at a Zen temple in Japan, Foucault remarked that this was “the end of the era of Western philosophy. Thus if philosophy of the future exists, it must be born outside of Europe or equally born in consequence of meetings and impacts between Europe and non-Europe” (1999, p. 113). Later that year, Foucault went to Iran “to be there at the birth of ideas.” He wrote that the new “Muslim” style of politics could signal the beginning of a new form of “political spirituality,” not just for the Middle East, but also for Europe, which had adopted a secular politics ever since the French Revolution. As he wrote in Corriere della sera in November 1978: There are more ideas on earth than intellectuals imagine. And these ideas are more active, stronger, more resistant, more passionate than “politicians” think. We have to be there at the birth of ideas, the bursting outward of their force: not in books expressing them, but in events manifesting this force, in struggles carried on around ideas, for or against them. Ideas do not rule the world. But it is because the world has ideas (and because it constantly produces them) that it is not passively ruled by those who are its leaders or those who would like to teach it, once and for all, what it must think. This is the direction we want these “journalistic reports” to take. An analysis of thought will be linked to an analysis of what is happening. Intellectuals will work together with journalists at the point where ideas and events intersect. (cited in Eribon [1989] 1991, p. 282) In addition to Corriere della Sera, Foucault wrote on Iran in French newspapers and journals, such as the daily Le Monde and the widely circulated leftist weekly Nouvel Observateur. Iranian student activists translated at least one of his essays into Persian and posted it on the walls of Tehran University in the fall of 1978. In spring 1979, the Iranian Writers Association published an interview with Foucault from the previous September on the concept of revolution and the role of the intellectual. All of Foucault’s writings and interviews on Iran are published in English in their entirety for the first time in the appendix to this volume, alongside those of some of his critics. Foucault staked out a series of distinctive political and theoretical positions on the Iranian Revolution. In part because only three of his fifteen articles and interviews on Iran have appeared in English, they have generated little discussion in the English-speaking world. But this itself is curious. Why, given the wide accessibility in English of even his interviews and other minor writings, have these texts not previously been made available to the English-speaking public, especially given the wide interest in Foucault by scholars of non-European societies? Many scholars of Foucault view these writings as aberrant or the product of a political mistake. We will suggest that Foucault’s writings on Iran were in fact closely related to his general theoretical writings on the discourses of power and the hazards of modernity. We will also argue that Foucault’s experience in Iran left a lasting impact on his subsequent oeuvre and that one cannot understand the sudden turn in Foucault’s writings in the 1980s without recognizing the significance of the Iranian episode and his more general preoccupation with the Orient. Long before most other commentators, Foucault understood that Iran was witnessing a singular kind of revolution. Early on, he predicted that this revolution would not follow the model of other modern revolutions. He wrote that it was organized around a sharply different concept, which he called “political spirituality.” Foucault recognized the enormous power of the new discourse of militant Islam, not just for Iran, but for the world. He showed that the new Islamist movement aimed at a fundamental cultural, social, and political break with the modern Western order, as well as with the Soviet Union and China: As an “Islamic” movement, it can set the entire region afire, overturn the most unstable regimes, and disturb the most solid. Islam — which is not simply a religion, but an entire way of life, an adherence to a history and a civilization — has a good chance to become a gigantic powder keg, at the level of hundreds of millions of men…. In fact, it is also important to recognize that the demand for the “legitimate rights of the Palestinian people” hardly stirred the Arab peoples. What would it be if this cause encompassed the dynamism of an Islamic movement, something much stronger than those with a Marxist, Leninist, or Maoist character? (this edition, p. 241) He also noted presciently that such a discourse would “alter the global strategic equilibrium” (this edition, p. 241) Foucault’s experience in Iran contributed to a turning point in his thought. In the late 1970s, he was moving from a preoccupation with technologies of domination to a new interest in what he termed the technologies of the self, as the foundation for a new form of spirituality and resistance to power. We argue that the Iranian Revolution had a lasting impact on his late writing in several ways. In his Iran writings, Foucault emphasized the deployment of certain instruments of modernity as means of resistance. He called attention to the innovative uses Islamists made of overseas radio broadcasts and cassettes. This blending of more traditional religious discourses with modern means of communication had helped to galvanize the revolutionary movement and ultimately paralyzed the modern and authoritarian Pahlavi regime. Foucault was also fascinated by the appropriation of Shi’ite myths of martyrdom and rituals of penitence by large parts of the revolutionary movement and their willingness to face death in their single-minded goal of overthrowing the Pahlavi regime. Later, in his discussion of an “aesthetics of existence” — practices that could be refashioned for our time and serve as the foundation for a new form of spirituality — Foucault often referred to Greco-Roman texts and early Christian practices. However, many of these practices also had a strong resemblance to what he saw in Iran. Additionally, many scholars have wondered about Foucault’s sudden turn to the ancient Greco-Roman world in volumes II and III of History of Sexuality, and his interest in uncovering male homosexual practices in this era. We would suggest an “Oriental” appropriation here as well. Foucault’s description of a male “ethics of love” in the Greco-Roman world greatly resembles some existing male homosexual practices of the Middle East and North Africa. Foucault’s foray into the Greco-Roman world might, therefore, have been related to his longstanding fascination with ars erotica and especially the erotic arts of the East, since Foucault sometimes combined the discussion of sexual practices of the contemporary East with those of the classical Greco-Roman society. The Iranian experience also raises some questions about Foucault’s overall approach to modernity. First, it is often assumed that Foucault’s suspicion of utopianism, his hostility to grand narratives and universals, and his stress on difference and singularity rather than totality, would make him less likely than his predecessors on the Left to romanticize an authoritarian politics that promised radically to refashion from above the lives and thought of a people, for its ostensible benefit. However, his Iran writings showed that Foucault was not immune to the type of illusions that so many Western leftists had held toward the Soviet Union and later, China. Foucault did not anticipate the birth of yet another modern state where old religious technologies of domination could be refashioned and institutionalized; this was a state that propounded a traditionalist ideology, but equipped itself with modern technologies of organization, surveillance, warfare, and propaganda. Second, Foucault’s highly problematic relationship to feminism becomes more than an intellectual lacuna in the case of Iran. On a few occasions, Foucault reproduced statements he had heard from religious figures on gender relations in a possible future Islamic Republic, but he never questioned the “separate but equal” message of the Islamists. Foucault also dismissed feminist premonitions that the Revolution was headed in a dangerous direction, and he seemed to regard such warnings as little more than Orientalist attacks on Islam, thereby depriving himself of a more balanced perspective toward the events in Iran. At a more general level, Foucault remained insensitive toward the diverse ways in which power affected women, as against men. He ignored the fact that those most traumatized by the premodern disciplinary practices were often women and children, who were oppressed in the name of tradition, obligation, or honor. In chapter one, we root his indifference to Iranian women in the problematic stances toward gender in his better-known writings, while in chapters three and four, we discuss Foucault’s response to attacks by Iranian and French feminists on his Iran writings themselves. Third, an examination of Foucault’s writings provides more support for the frequently articulated criticism that his one-sided critique of modernity needs to be seriously reconsidered, especially from the vantage point of many non-Western societies. Indeed, there are some indications that Foucault himself was moving in such a direction. In his 1984 essay “What Is Enlightenment?” Foucault put forth a position on the Enlightenment that was more nuanced than before, also moving from a two-pronged philosophy concerned with knowledge and power to a three-pronged one that included ethics. However, the limits of his ethics of moderation with regard to gender and sexuality need to be explored and this is the subject of the last chapter of this book. As against Foucault, some French leftists were very critical of the Iranian Revolution early on. Beginning in December 1978 with a series of articles that appeared on the front page of Le Monde, the noted Middle East scholar and leftist commentator Maxime Rodinson, known for his classic biography of Muhammad, published some hard-hitting critiques of Islamism in Iran as a form of “semi-archaic fascism” (this volume, p. 233). As Rodinson later revealed, he was specifically targeting Foucault in these articles, which drew on Max Weber’s notion of charisma, Marx’s concepts of class and ideology, and a range of scholarship on Iran and Islam. In March 1979, Foucault’s writings on Iran came under increasing attack in the wake of the new regime’s executions of homosexual men and especially the large demonstrations by Iranian women on the streets of Tehran against Khomeini’s directives for compulsory veiling. In addition, France’s best-known feminist, the existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, protested the Khomeini regime’s suppression of women’s rights and sent a message of solidarity to Iranian women (this volume, pp. 246-247). However, Foucault refused to respond to the new attacks, issuing only a mild criticism of human rights in Iran that refrained from any mention of women’s rights or gay rights, before lapsing into silence on Iran.

~~~~~~~~~

From the Appendix

What Are the Iranians Dreaming About? By Michel Foucault

Translated by Kevin B. Anderson and Karen de Bruin

First published in Le Nouvel Observateur, October 16-22, 1978.

“They will never let go of us of their own will. No more than they did in Vietnam.” I wanted to respond that they are even less ready to let go of you than Vietnam because of oil, because of the Middle East. Today they seem ready, after Camp David, to concede Lebanon to Syrian domination and therefore to Soviet influence, but would the United States be ready to deprive itself of a position that, according to circumstance, would allow them to intervene from the East or to monitor the peace? Will the Americans push the shah toward a new trial of strength, a second “Black Friday”? The recommencement of classes at the university, the recent strikes, the disturbances that are beginning once again, and next month’s religious festivals, could create such an opportunity. The man with the iron hand is Moghadam, the current leader of the SAVAK. This is the backup plan, which for the moment is neither the most desirable nor the most likely. It would be uncertain: While some generals could be counted on, it is not clear if the army could be. From a certain point of view, it would be useless, for there is no “communist threat”: not from outside, since it has been agreed for the past twenty-five years that the USSR would not lay a hand on Iran; not from inside, because hatred for the Americans is equaled only by fear of the Soviets. Whether advisers to the shah, American experts, regime technocrats, or groups from the political opposition (be they the National Front or more “socialist-oriented” men), during these last weeks everyone has agreed with more or less good grace to attempt an “accelerated internal liberalization,” or to let it occur. At present, the Spanish model is the favorite of the political leadership. Is it adaptable to Iran? There are many technical problems. There are questions concerning the date: Now, or later, after another violent incident? There are questions concerning individual persons: With or without the shah? Maybe with the son, the wife? Is not former prime minister Amini, the old diplomat pegged to lead the operation, already worn out?

The King and the Saint

There are substantial differences between Iran and Spain, however. The failure of economic development in Iran prevented the laying of a basis for a liberal, modern, westernized regime. Instead, there arose an immense movement from below, which exploded this year, shaking up the political parties that were being slowly reconstituted. This movement has just thrown half a million men into the streets of Tehran, up against machine guns and tanks. Not only did they shout, “Death to the Shah,” but also “Islam, Islam, Khomeini, We Will Follow You,” and even “Khomeini for King.” The situation in Iran can be understood as a great joust under traditional emblems, those of the king and the saint, the armed ruler and the destitute exile, the despot faced with the man who stands up bare-handed and is acclaimed by a people. This image has its own power, but it also speaks to a reality to which millions of dead have just subscribed. The notion of a rapid liberalization without a rupture in the power structure presupposes that the movement from below is being integrated into the system, or that it is being neutralized. Here, one must first discern where and how far the movement intends to go. However, yesterday in Paris, where he had sought refuge, and in spite of many pressures, Ayatollah Khomeini “ruined it all.” He sent out an appeal to the students, but he was also addressing the Muslim community and the army, asking that they oppose in the name of the Quran and in the name of nationalism these compromises concerning elections, a constitution, and so forth. Is a long-foreseen split taking place within the opposition to the shah? The “politicians” of the opposition try to be reassuring: “It is good,” they say. “Khomeini, by raising the stakes, reinforces us in the face of the shah and the Americans. Anyway, his name is only a rallying cry, for he has no program. Do not forget that, since 1963, political parties have been muzzled. At the moment, we are rallying to Khomeini, but once the dictatorship is abolished, all this mist will dissipate. Authentic politics will take command, and we will soon forget the old preacher.” But all the agitation this weekend around the hardly clandestine residence of the ayatollah in the suburbs of Paris, as well as the coming and going of “important” Iranians, all of this contradicted this somewhat hasty optimism. It all proved that people believed in the power of the mysterious current that flowed between an old man who had been exiled for fifteen years and his people, who invoke his name. The nature of this current has intrigued me since I learned about it a few months ago, and I was a little weary, I must confess, of hearing so many clever experts repeating: “We know what they don’t want, but they still do not know what they want.” “What do you want?” It is with this single question in mind that I walked the streets of Tehran and Qom in the days immediately following the disturbances. I was careful not to ask professional politicians this question. I chose instead to hold sometimes-lengthy conversations with religious leaders, students, intellectuals interested in the problems of Islam, and also with former guerilla fighters who had abandoned the armed struggle in 1976 and had decided to work in a totally different fashion, inside the traditional society. “What do you want?” During my entire stay in Iran, I did not hear even once the word “revolution,” but four out of five times, someone would answer, “An Islamic government.” This was not a surprise. Ayatollah Khomeini had already given this as his pithy response to journalists and the response remained at that point. What precisely does this mean in a country like Iran, which has a large Muslim majority but is neither Arab nor Sunni and which is therefore less susceptible than some to Pan-Islamism or Pan-Arabism? Indeed, Shiite Islam exhibits a number of characteristics that are likely to give the desire for an “Islamic government” a particular coloration. Concerning its organization, there is an absence of hierarchy in the clergy, a certain independence of the religious leaders from one another, but a dependence (even a financial one) on those who listen to them, and an importance given to purely spiritual authority. The role, both echoing and guiding, that the clergy must play in order to sustain its influence-this is what the organization is all about. As for Shi’ite doctrine, there is the principle that truth was not completed and sealed by the last prophet. After Muhammad, another cycle of revelation begins, the unfinished cycle of the imams, who, through their words, their example, as well as their martyrdom, carry a light, always the same and always changing. It is this light that is capable of illuminating the law from the inside. The latter is made not only to be conserved, but also to release over time the spiritual meaning that it holds. Although invisible before his promised return, the Twelfth Imam is neither radically nor fatally absent. It is the people themselves who make him come back, insofar as the truth to which they awaken further enlightens them. It is often said that for Shi’ism, all power is bad if it is not the power of the Imam. As we can see, things are much more complex. This is what Ayatollah Shariatmadari told me in the first few minutes of our meeting: “We are waiting for the return of the Imam, which does not mean that we are giving up on the possibility of a good government. This is also what you Christians are endeavoring to achieve, although you are waiting for Judgment Day.” As if to lend a greater authenticity to his words, the ayatollah was surrounded by several members of the Committee on Human Rights in Iran when he received me. One thing must be clear. By “Islamic government,” nobody in Iran means a political regime in which the clerics would have a role of supervision or control. To me, the phrase “Islamic government” seemed to point to two orders of things. “A utopia,” some told me without any pejorative implication. “An ideal,” most of them said to me. At any rate, it is something very old and also very far into the future, a notion of coming back to what Islam was at the time of the Prophet, but also of advancing toward a luminous and distant point where it would be possible to renew fidelity rather than maintain obedience. In pursuit of this ideal, the distrust of legalism seemed to me to be essential, along with a faith in the creativity of Islam. A religious authority explained to me that it would require long work by civil and religious experts, scholars, and believers in order to shed light on all the problems to which the Quran never claimed to give a precise response. But one can find some general directions here: Islam values work; no one can be deprived of the fruits of his labor; what must belong to all (water, the subsoil) shall not be appropriated by anyone. With respect to liberties, they will be respected to the extent that their exercise will not harm others; minorities will be protected and free to live as they please on the condition that they do not injure the majority; between men and women there will not be inequality with respect to rights, but difference, since there is a natural difference. With respect to politics, decisions should be made by the majority, the leaders should be responsible to the people, and each person, as it is laid out in the Quran, should be able to stand up and hold accountable he who governs. It is often said that the definitions of an Islamic government are imprecise. On the contrary, they seemed to me to have a familiar but, I must say, not too reassuring clarity. “These are basic formulas for democracy, whether bourgeois or revolutionary,” I said. “Since the eighteenth century now, we have not ceased to repeat them, and you know where they have led.” But I immediately received the following reply: “The Quran had enunciated them way before your philosophers, and if the Christian and industrialized West lost their meaning, Islam will know how to preserve their value and their efficacy.” When Iranians speak of Islamic government; when, under the threat of bullets, they transform it into a slogan of the streets; when they reject in its name, perhaps at the risk of a bloodbath, deals arranged by parties and politicians, they have other things on their minds than these formulas from everywhere and nowhere. They also have other things in their hearts. I believe that they are thinking about a reality that is very near to them, since they themselves are its active agents. It is first and foremost about a movement that aims to give a permanent role in political life to the traditional structures of Islamic society. An Islamic government is what will allow the continuing activity of the thousands of political centers that have been spawned in mosques and religious communities in order to resist the shah’s regime. I was given an example. Ten years ago, an earthquake hit Ferdows. The entire city had to be reconstructed, but since the plan that had been selected was not to the satisfaction of most of the peasants and the small artisans, they seceded. Under the guidance of a religious leader, they went on to found their city a little further away. They had collected funds in the entire region. They had collectively chosen places to settle, arranged a water supply, and organized cooperatives. They had called their city Islamiyeh. The earthquake had been an opportunity to use religious structures not only as centers of resistance, but also as sources for political creation. This is what one dreams about [songe] when one speaks of Islamic government.

The Invisible Present

But one dreams [songe] also of another movement, which is the inverse and the converse of the first. This is one that would allow the introduction of a spiritual dimension into political life, in order that it would not be, as always, the obstacle to spirituality, but rather its receptacle, its opportunity, and its ferment. This is where we encounter a shadow that haunts all political and religious life in Iran today: that of Ali Shariati, whose death two years ago gave him the position, so privileged in Shi’ism, of the invisible Present, of the ever-present Absent. During his studies in Europe, Shariati, who came from a religious milieu, had been in contact with leaders of the Algerian Revolution, with various left-wing Christian movements, with an entire current of non-Marxist socialism. (He had attended Gurvitch’s classes.) He knew the work of Fanon and Massignon. He came back to Mashhad, where he taught that the true meaning of Shi’ism should not be sought in a religion that had been institutionalized since the seventeenth century, but in the sermons of social justice and equality that had already been preached by the first imam. His “luck” was that persecution forced him to go to Tehran and to have to teach outside of the university, in a room prepared for him under the protection of a mosque. There, he addressed a public that was his, and that could soon be counted in the thousands: students, mullahs, intellectuals, modest people from the neighborhood of the bazaar, and people passing through from the provinces. Shariati died like a martyr, hunted and with his books banned. He gave himself up when his father was arrested instead of him. After a year in prison, shortly after having gone into exile, he died in a manner that very few accept as having stemmed from natural causes. The other day, at the big protest in Tehran, Shariati’s name was the only one that was called out, besides that of Khomeini.

The Inventors of the State

I do not feel comfortable speaking of Islamic government as an “idea” or even as an “ideal.” Rather, it impressed me as a form of “political will.” It impressed me in its effort to politicize structures that are inseparably social and religious in response to current problems. It also impressed me in its attempt to open a spiritual dimension in politics. In the short term, this political will raises two questions: 1. Is it sufficiently intense now, and is its determination clear enough to prevent an “Amini solution,” which has in its favor (or against it, if one prefers) the fact that it is acceptable to the shah, that it is recommended by the foreign powers, that it aims at a Western-style parliamentary regime, and that it would undoubtedly privilege the Islamic religion? 2. Is this political will rooted deeply enough to become a permanent factor in the political life of Iran, or will it dissipate like a cloud when the sky of political reality will have finally cleared, and when we will be able to talk about programs, parties, a constitution, plans, and so forth? Politicians might say that the answers to these two questions determine much of their tactics today. With respect to this “political will,” however, there are also two questions that concern me even more deeply. One bears on Iran and its peculiar destiny. At the dawn of history, Persia invented the state and conferred its models on Islam. Its administrators staffed the caliphate. But from this same Islam, it derived a religion that gave to its people infinite resources to resist state power. In this will for an “Islamic government,” should one see a reconciliation, a contradiction, or the threshold of something new? The other question concerns this little corner of the earth whose land, both above and below the surface, has strategic importance at a global level. For the people who inhabit this land, what is the point of searching, even at the cost of their own lives, for this thing whose possibility we have forgotten since the Renaissance and the great crisis of Christianity, a political spirituality. I can already hear the French laughing, but I know that they are wrong.

Translation

Book Reviews: English

Javier Sethness, “Why Did Foucault Disregard Iranian Feminists in His Support for Khomeini?” Truthout, Sept. 13, 2016 Sarah Amsler, British Journal of Sociology, Volume 57, Issue3, 2006 James Bernauer, An uncritical Foucault? Foucault and the Iranian Revolution, Philosophy & Social Criticism, Vol 32, No. 6. 2006 Jeremy Carrette, University of Kent, April 19, 2006 Babak Elahi, East-Struck: Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson’s Foucault and the Iranian Revolutionin Context, June 6, 2007 David Farber, “His Own Private Iran,” Bookforum, April-May 2005 David Frum, David Frum’s Diary, National Review Online, August 5, 2007 Lois McNay, University of Oxford, 2007 Moghadam, Valentine M., Perspectives on Politics, UNESCO, Volume 5, No. 1, March 2007 Danny Postel, Filling the Void, The Common Review, Vol. 4, No. 2 Vijay Prashad, Iranian Studies, Volume 40, No. 2, April 2007 Ahmad Sadri, Contemporary Sociology, Volume 35, No. 5 Faeghe Shirazi, Feminism and the Rule of Fundamentalism in the Islamic Republic of Iran, International Feminist Journal of Politics, Volume 9, No. 3, September 2007 Saeed Ur-Rehman, “Engaging Islam and Postmodernism,” The Friday Times, Lahore,Pakistan, January 20-26, 2006 Wesley Yang, “The Philosopher and the Ayatollah,” Boston Globe, June 12, 2005. Rafia Zakaria, The “other” Orientalism, Frontline: India’s National Magazine, Volume 22 – Issue 26, Dec. 17 – 30, 2005

.

Book Reviews: Other Languages

(Portuguese) Antonio Gonçalves Filho, “Foucault e o islà, mistura explosiva,” Estadào (Sao Paulo), March 5, 2011 (French) Azadeh Kian-Thiébaut, Abstracta Iranica, 2005 (Persian) Mehdi Khalji, BBC, Feb. 06, 2006 (Swedish) Trobjon Elensky, Dagens Nyheter, October 26, 2005

Overview

This study illuminates Foucault’s support of the Islamist movement and how his experiences in Iran contributed to a turning point in his thought, influencing his ideas on the Enlightenment, homosexuality, and his search for political spirituality. Co-authored with Kevin B. Anderson. In 1978, as the protests against the Shah of Iran reached their zenith, philosopher Michel Foucault was working as a special correspondent for Corriere della Sera and le Nouvel Observateur. During his little-known stint as a journalist, Foucault traveled to Iran, met with leaders like Ayatollah Khomeini, and wrote a series of articles on the revolution. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution is the first book-length analysis of these essays on Iran, the majority of which have never before appeared in English. Accompanying the analysis are annotated translations of the Iran writings in their entirety and the at times blistering responses from such contemporaneous critics as Middle East scholar Maxime Rodinson as well as comments on the revolution by feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. In this important and controversial account, Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson illuminate Foucault’s support of the Islamist movement. They also show how Foucault’s experiences in Iran contributed to a turning point in his thought, influencing his ideas on the Enlightenment, homosexuality, and his search for political spirituality. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution informs current discussion on the divisions that have reemerged among Western intellectuals over the response to radical Islamism after September 11. Foucault’s provocative writings are thus essential for understanding the history and the future of the West’s relationship with Iran and, more generally, to political Islam. In their examination of these journalistic pieces, Afary and Anderson offer a surprising glimpse into the mind of a celebrated thinker. Introduction Part I Foucault’s Discourse: On Pinnacles and Pitfalls 1. The Paradoxical World of Foucault: The Modern and the Traditional Social Orders 2. Processions, Passion Plays, and Rites of Penance: Foucault, Shi’ism, and Early Christian Rituals Part II Foucault’s Writings on the Iranian Revolution and After 3. The Visits to Iran and the Controversies with “Atoussa H.” and Maxime Rodinson 4. Debating the Outcome of the Revolution, Especially on Women’s Rights 5. Foucault, Gender, and Male Homosexualities in Mediterranean and Muslim Societies Epilogue: From the Iranian Revolution to September 11, 2001 Appendix: Foucault and His Critics, an Annotated Translation

~~~~~~~~~

From the Introduction

Throughout his life, Michel Foucault’s concept of authenticity meant looking at situations where people lived dangerously and flirted with death, the site where creativity originated. In the tradition of Friedrich Nietzsche and Georges Bataille, Foucault had embraced the artist who pushed the limits of rationality and he wrote with great passion in defense of irrationalities that broke new boundaries. In 1978, Foucault found such transgressive powers in the revolutionary figure of Ayatollah Khomeini and the millions who risked death as they followed him in the course of the Revolution. He knew that such “limit” experiences could lead to new forms of creativity and he passionately threw in his support. This was Foucault’s only first-hand experience of revolution and it led to his most extensive set of writings on a non-Western society. Foucault first visited Iran in September 1978 and then met with Khomeini at his exile residence outside Paris in October. Foucault traveled to Iran for a second visit in November, when the revolutionary movement against the shah was reaching its zenith. During these two trips, Foucault was commissioned as a special correspondent of the leading Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, with his articles appearing on page one of that paper. Foucault’s interest in the Iranian Revolution was much more than a journalistic curiosity. His earlier work had shown a consistent though subtle affinity for the Orient and the more traditional social norms of the East, as well as a messianic preoccupation with Eastern thought. Foucault believed that the demise of colonialism by the 1960s had brought Western thought to a turning point and to a crisis. During a 1978 encounter at a Zen temple in Japan, Foucault remarked that this was “the end of the era of Western philosophy. Thus if philosophy of the future exists, it must be born outside of Europe or equally born in consequence of meetings and impacts between Europe and non-Europe” (1999, p. 113). Later that year, Foucault went to Iran “to be there at the birth of ideas.” He wrote that the new “Muslim” style of politics could signal the beginning of a new form of “political spirituality,” not just for the Middle East, but also for Europe, which had adopted a secular politics ever since the French Revolution. As he wrote in Corriere della sera in November 1978: There are more ideas on earth than intellectuals imagine. And these ideas are more active, stronger, more resistant, more passionate than “politicians” think. We have to be there at the birth of ideas, the bursting outward of their force: not in books expressing them, but in events manifesting this force, in struggles carried on around ideas, for or against them. Ideas do not rule the world. But it is because the world has ideas (and because it constantly produces them) that it is not passively ruled by those who are its leaders or those who would like to teach it, once and for all, what it must think. This is the direction we want these “journalistic reports” to take. An analysis of thought will be linked to an analysis of what is happening. Intellectuals will work together with journalists at the point where ideas and events intersect. (cited in Eribon [1989] 1991, p. 282) In addition to Corriere della Sera, Foucault wrote on Iran in French newspapers and journals, such as the daily Le Monde and the widely circulated leftist weekly Nouvel Observateur. Iranian student activists translated at least one of his essays into Persian and posted it on the walls of Tehran University in the fall of 1978. In spring 1979, the Iranian Writers Association published an interview with Foucault from the previous September on the concept of revolution and the role of the intellectual. All of Foucault’s writings and interviews on Iran are published in English in their entirety for the first time in the appendix to this volume, alongside those of some of his critics. Foucault staked out a series of distinctive political and theoretical positions on the Iranian Revolution. In part because only three of his fifteen articles and interviews on Iran have appeared in English, they have generated little discussion in the English-speaking world. But this itself is curious. Why, given the wide accessibility in English of even his interviews and other minor writings, have these texts not previously been made available to the English-speaking public, especially given the wide interest in Foucault by scholars of non-European societies? Many scholars of Foucault view these writings as aberrant or the product of a political mistake. We will suggest that Foucault’s writings on Iran were in fact closely related to his general theoretical writings on the discourses of power and the hazards of modernity. We will also argue that Foucault’s experience in Iran left a lasting impact on his subsequent oeuvre and that one cannot understand the sudden turn in Foucault’s writings in the 1980s without recognizing the significance of the Iranian episode and his more general preoccupation with the Orient. Long before most other commentators, Foucault understood that Iran was witnessing a singular kind of revolution. Early on, he predicted that this revolution would not follow the model of other modern revolutions. He wrote that it was organized around a sharply different concept, which he called “political spirituality.” Foucault recognized the enormous power of the new discourse of militant Islam, not just for Iran, but for the world. He showed that the new Islamist movement aimed at a fundamental cultural, social, and political break with the modern Western order, as well as with the Soviet Union and China: As an “Islamic” movement, it can set the entire region afire, overturn the most unstable regimes, and disturb the most solid. Islam — which is not simply a religion, but an entire way of life, an adherence to a history and a civilization — has a good chance to become a gigantic powder keg, at the level of hundreds of millions of men…. In fact, it is also important to recognize that the demand for the “legitimate rights of the Palestinian people” hardly stirred the Arab peoples. What would it be if this cause encompassed the dynamism of an Islamic movement, something much stronger than those with a Marxist, Leninist, or Maoist character? (this edition, p. 241) He also noted presciently that such a discourse would “alter the global strategic equilibrium” (this edition, p. 241) Foucault’s experience in Iran contributed to a turning point in his thought. In the late 1970s, he was moving from a preoccupation with technologies of domination to a new interest in what he termed the technologies of the self, as the foundation for a new form of spirituality and resistance to power. We argue that the Iranian Revolution had a lasting impact on his late writing in several ways. In his Iran writings, Foucault emphasized the deployment of certain instruments of modernity as means of resistance. He called attention to the innovative uses Islamists made of overseas radio broadcasts and cassettes. This blending of more traditional religious discourses with modern means of communication had helped to galvanize the revolutionary movement and ultimately paralyzed the modern and authoritarian Pahlavi regime. Foucault was also fascinated by the appropriation of Shi’ite myths of martyrdom and rituals of penitence by large parts of the revolutionary movement and their willingness to face death in their single-minded goal of overthrowing the Pahlavi regime. Later, in his discussion of an “aesthetics of existence” — practices that could be refashioned for our time and serve as the foundation for a new form of spirituality — Foucault often referred to Greco-Roman texts and early Christian practices. However, many of these practices also had a strong resemblance to what he saw in Iran. Additionally, many scholars have wondered about Foucault’s sudden turn to the ancient Greco-Roman world in volumes II and III of History of Sexuality, and his interest in uncovering male homosexual practices in this era. We would suggest an “Oriental” appropriation here as well. Foucault’s description of a male “ethics of love” in the Greco-Roman world greatly resembles some existing male homosexual practices of the Middle East and North Africa. Foucault’s foray into the Greco-Roman world might, therefore, have been related to his longstanding fascination with ars erotica and especially the erotic arts of the East, since Foucault sometimes combined the discussion of sexual practices of the contemporary East with those of the classical Greco-Roman society. The Iranian experience also raises some questions about Foucault’s overall approach to modernity. First, it is often assumed that Foucault’s suspicion of utopianism, his hostility to grand narratives and universals, and his stress on difference and singularity rather than totality, would make him less likely than his predecessors on the Left to romanticize an authoritarian politics that promised radically to refashion from above the lives and thought of a people, for its ostensible benefit. However, his Iran writings showed that Foucault was not immune to the type of illusions that so many Western leftists had held toward the Soviet Union and later, China. Foucault did not anticipate the birth of yet another modern state where old religious technologies of domination could be refashioned and institutionalized; this was a state that propounded a traditionalist ideology, but equipped itself with modern technologies of organization, surveillance, warfare, and propaganda. Second, Foucault’s highly problematic relationship to feminism becomes more than an intellectual lacuna in the case of Iran. On a few occasions, Foucault reproduced statements he had heard from religious figures on gender relations in a possible future Islamic Republic, but he never questioned the “separate but equal” message of the Islamists. Foucault also dismissed feminist premonitions that the Revolution was headed in a dangerous direction, and he seemed to regard such warnings as little more than Orientalist attacks on Islam, thereby depriving himself of a more balanced perspective toward the events in Iran. At a more general level, Foucault remained insensitive toward the diverse ways in which power affected women, as against men. He ignored the fact that those most traumatized by the premodern disciplinary practices were often women and children, who were oppressed in the name of tradition, obligation, or honor. In chapter one, we root his indifference to Iranian women in the problematic stances toward gender in his better-known writings, while in chapters three and four, we discuss Foucault’s response to attacks by Iranian and French feminists on his Iran writings themselves. Third, an examination of Foucault’s writings provides more support for the frequently articulated criticism that his one-sided critique of modernity needs to be seriously reconsidered, especially from the vantage point of many non-Western societies. Indeed, there are some indications that Foucault himself was moving in such a direction. In his 1984 essay “What Is Enlightenment?” Foucault put forth a position on the Enlightenment that was more nuanced than before, also moving from a two-pronged philosophy concerned with knowledge and power to a three-pronged one that included ethics. However, the limits of his ethics of moderation with regard to gender and sexuality need to be explored and this is the subject of the last chapter of this book. As against Foucault, some French leftists were very critical of the Iranian Revolution early on. Beginning in December 1978 with a series of articles that appeared on the front page of Le Monde, the noted Middle East scholar and leftist commentator Maxime Rodinson, known for his classic biography of Muhammad, published some hard-hitting critiques of Islamism in Iran as a form of “semi-archaic fascism” (this volume, p. 233). As Rodinson later revealed, he was specifically targeting Foucault in these articles, which drew on Max Weber’s notion of charisma, Marx’s concepts of class and ideology, and a range of scholarship on Iran and Islam. In March 1979, Foucault’s writings on Iran came under increasing attack in the wake of the new regime’s executions of homosexual men and especially the large demonstrations by Iranian women on the streets of Tehran against Khomeini’s directives for compulsory veiling. In addition, France’s best-known feminist, the existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, protested the Khomeini regime’s suppression of women’s rights and sent a message of solidarity to Iranian women (this volume, pp. 246-247). However, Foucault refused to respond to the new attacks, issuing only a mild criticism of human rights in Iran that refrained from any mention of women’s rights or gay rights, before lapsing into silence on Iran.

~~~~~~~~~

From the Appendix

What Are the Iranians Dreaming About? By Michel Foucault

Translated by Kevin B. Anderson and Karen de Bruin

First published in Le Nouvel Observateur, October 16-22, 1978.

“They will never let go of us of their own will. No more than they did in Vietnam.” I wanted to respond that they are even less ready to let go of you than Vietnam because of oil, because of the Middle East. Today they seem ready, after Camp David, to concede Lebanon to Syrian domination and therefore to Soviet influence, but would the United States be ready to deprive itself of a position that, according to circumstance, would allow them to intervene from the East or to monitor the peace? Will the Americans push the shah toward a new trial of strength, a second “Black Friday”? The recommencement of classes at the university, the recent strikes, the disturbances that are beginning once again, and next month’s religious festivals, could create such an opportunity. The man with the iron hand is Moghadam, the current leader of the SAVAK. This is the backup plan, which for the moment is neither the most desirable nor the most likely. It would be uncertain: While some generals could be counted on, it is not clear if the army could be. From a certain point of view, it would be useless, for there is no “communist threat”: not from outside, since it has been agreed for the past twenty-five years that the USSR would not lay a hand on Iran; not from inside, because hatred for the Americans is equaled only by fear of the Soviets. Whether advisers to the shah, American experts, regime technocrats, or groups from the political opposition (be they the National Front or more “socialist-oriented” men), during these last weeks everyone has agreed with more or less good grace to attempt an “accelerated internal liberalization,” or to let it occur. At present, the Spanish model is the favorite of the political leadership. Is it adaptable to Iran? There are many technical problems. There are questions concerning the date: Now, or later, after another violent incident? There are questions concerning individual persons: With or without the shah? Maybe with the son, the wife? Is not former prime minister Amini, the old diplomat pegged to lead the operation, already worn out?

The King and the Saint

There are substantial differences between Iran and Spain, however. The failure of economic development in Iran prevented the laying of a basis for a liberal, modern, westernized regime. Instead, there arose an immense movement from below, which exploded this year, shaking up the political parties that were being slowly reconstituted. This movement has just thrown half a million men into the streets of Tehran, up against machine guns and tanks. Not only did they shout, “Death to the Shah,” but also “Islam, Islam, Khomeini, We Will Follow You,” and even “Khomeini for King.” The situation in Iran can be understood as a great joust under traditional emblems, those of the king and the saint, the armed ruler and the destitute exile, the despot faced with the man who stands up bare-handed and is acclaimed by a people. This image has its own power, but it also speaks to a reality to which millions of dead have just subscribed. The notion of a rapid liberalization without a rupture in the power structure presupposes that the movement from below is being integrated into the system, or that it is being neutralized. Here, one must first discern where and how far the movement intends to go. However, yesterday in Paris, where he had sought refuge, and in spite of many pressures, Ayatollah Khomeini “ruined it all.” He sent out an appeal to the students, but he was also addressing the Muslim community and the army, asking that they oppose in the name of the Quran and in the name of nationalism these compromises concerning elections, a constitution, and so forth. Is a long-foreseen split taking place within the opposition to the shah? The “politicians” of the opposition try to be reassuring: “It is good,” they say. “Khomeini, by raising the stakes, reinforces us in the face of the shah and the Americans. Anyway, his name is only a rallying cry, for he has no program. Do not forget that, since 1963, political parties have been muzzled. At the moment, we are rallying to Khomeini, but once the dictatorship is abolished, all this mist will dissipate. Authentic politics will take command, and we will soon forget the old preacher.” But all the agitation this weekend around the hardly clandestine residence of the ayatollah in the suburbs of Paris, as well as the coming and going of “important” Iranians, all of this contradicted this somewhat hasty optimism. It all proved that people believed in the power of the mysterious current that flowed between an old man who had been exiled for fifteen years and his people, who invoke his name. The nature of this current has intrigued me since I learned about it a few months ago, and I was a little weary, I must confess, of hearing so many clever experts repeating: “We know what they don’t want, but they still do not know what they want.” “What do you want?” It is with this single question in mind that I walked the streets of Tehran and Qom in the days immediately following the disturbances. I was careful not to ask professional politicians this question. I chose instead to hold sometimes-lengthy conversations with religious leaders, students, intellectuals interested in the problems of Islam, and also with former guerilla fighters who had abandoned the armed struggle in 1976 and had decided to work in a totally different fashion, inside the traditional society. “What do you want?” During my entire stay in Iran, I did not hear even once the word “revolution,” but four out of five times, someone would answer, “An Islamic government.” This was not a surprise. Ayatollah Khomeini had already given this as his pithy response to journalists and the response remained at that point. What precisely does this mean in a country like Iran, which has a large Muslim majority but is neither Arab nor Sunni and which is therefore less susceptible than some to Pan-Islamism or Pan-Arabism? Indeed, Shiite Islam exhibits a number of characteristics that are likely to give the desire for an “Islamic government” a particular coloration. Concerning its organization, there is an absence of hierarchy in the clergy, a certain independence of the religious leaders from one another, but a dependence (even a financial one) on those who listen to them, and an importance given to purely spiritual authority. The role, both echoing and guiding, that the clergy must play in order to sustain its influence-this is what the organization is all about. As for Shi’ite doctrine, there is the principle that truth was not completed and sealed by the last prophet. After Muhammad, another cycle of revelation begins, the unfinished cycle of the imams, who, through their words, their example, as well as their martyrdom, carry a light, always the same and always changing. It is this light that is capable of illuminating the law from the inside. The latter is made not only to be conserved, but also to release over time the spiritual meaning that it holds. Although invisible before his promised return, the Twelfth Imam is neither radically nor fatally absent. It is the people themselves who make him come back, insofar as the truth to which they awaken further enlightens them. It is often said that for Shi’ism, all power is bad if it is not the power of the Imam. As we can see, things are much more complex. This is what Ayatollah Shariatmadari told me in the first few minutes of our meeting: “We are waiting for the return of the Imam, which does not mean that we are giving up on the possibility of a good government. This is also what you Christians are endeavoring to achieve, although you are waiting for Judgment Day.” As if to lend a greater authenticity to his words, the ayatollah was surrounded by several members of the Committee on Human Rights in Iran when he received me. One thing must be clear. By “Islamic government,” nobody in Iran means a political regime in which the clerics would have a role of supervision or control. To me, the phrase “Islamic government” seemed to point to two orders of things. “A utopia,” some told me without any pejorative implication. “An ideal,” most of them said to me. At any rate, it is something very old and also very far into the future, a notion of coming back to what Islam was at the time of the Prophet, but also of advancing toward a luminous and distant point where it would be possible to renew fidelity rather than maintain obedience. In pursuit of this ideal, the distrust of legalism seemed to me to be essential, along with a faith in the creativity of Islam. A religious authority explained to me that it would require long work by civil and religious experts, scholars, and believers in order to shed light on all the problems to which the Quran never claimed to give a precise response. But one can find some general directions here: Islam values work; no one can be deprived of the fruits of his labor; what must belong to all (water, the subsoil) shall not be appropriated by anyone. With respect to liberties, they will be respected to the extent that their exercise will not harm others; minorities will be protected and free to live as they please on the condition that they do not injure the majority; between men and women there will not be inequality with respect to rights, but difference, since there is a natural difference. With respect to politics, decisions should be made by the majority, the leaders should be responsible to the people, and each person, as it is laid out in the Quran, should be able to stand up and hold accountable he who governs. It is often said that the definitions of an Islamic government are imprecise. On the contrary, they seemed to me to have a familiar but, I must say, not too reassuring clarity. “These are basic formulas for democracy, whether bourgeois or revolutionary,” I said. “Since the eighteenth century now, we have not ceased to repeat them, and you know where they have led.” But I immediately received the following reply: “The Quran had enunciated them way before your philosophers, and if the Christian and industrialized West lost their meaning, Islam will know how to preserve their value and their efficacy.” When Iranians speak of Islamic government; when, under the threat of bullets, they transform it into a slogan of the streets; when they reject in its name, perhaps at the risk of a bloodbath, deals arranged by parties and politicians, they have other things on their minds than these formulas from everywhere and nowhere. They also have other things in their hearts. I believe that they are thinking about a reality that is very near to them, since they themselves are its active agents. It is first and foremost about a movement that aims to give a permanent role in political life to the traditional structures of Islamic society. An Islamic government is what will allow the continuing activity of the thousands of political centers that have been spawned in mosques and religious communities in order to resist the shah’s regime. I was given an example. Ten years ago, an earthquake hit Ferdows. The entire city had to be reconstructed, but since the plan that had been selected was not to the satisfaction of most of the peasants and the small artisans, they seceded. Under the guidance of a religious leader, they went on to found their city a little further away. They had collected funds in the entire region. They had collectively chosen places to settle, arranged a water supply, and organized cooperatives. They had called their city Islamiyeh. The earthquake had been an opportunity to use religious structures not only as centers of resistance, but also as sources for political creation. This is what one dreams about [songe] when one speaks of Islamic government.

The Invisible Present

But one dreams [songe] also of another movement, which is the inverse and the converse of the first. This is one that would allow the introduction of a spiritual dimension into political life, in order that it would not be, as always, the obstacle to spirituality, but rather its receptacle, its opportunity, and its ferment. This is where we encounter a shadow that haunts all political and religious life in Iran today: that of Ali Shariati, whose death two years ago gave him the position, so privileged in Shi’ism, of the invisible Present, of the ever-present Absent. During his studies in Europe, Shariati, who came from a religious milieu, had been in contact with leaders of the Algerian Revolution, with various left-wing Christian movements, with an entire current of non-Marxist socialism. (He had attended Gurvitch’s classes.) He knew the work of Fanon and Massignon. He came back to Mashhad, where he taught that the true meaning of Shi’ism should not be sought in a religion that had been institutionalized since the seventeenth century, but in the sermons of social justice and equality that had already been preached by the first imam. His “luck” was that persecution forced him to go to Tehran and to have to teach outside of the university, in a room prepared for him under the protection of a mosque. There, he addressed a public that was his, and that could soon be counted in the thousands: students, mullahs, intellectuals, modest people from the neighborhood of the bazaar, and people passing through from the provinces. Shariati died like a martyr, hunted and with his books banned. He gave himself up when his father was arrested instead of him. After a year in prison, shortly after having gone into exile, he died in a manner that very few accept as having stemmed from natural causes. The other day, at the big protest in Tehran, Shariati’s name was the only one that was called out, besides that of Khomeini.

The Inventors of the State

I do not feel comfortable speaking of Islamic government as an “idea” or even as an “ideal.” Rather, it impressed me as a form of “political will.” It impressed me in its effort to politicize structures that are inseparably social and religious in response to current problems. It also impressed me in its attempt to open a spiritual dimension in politics. In the short term, this political will raises two questions: 1. Is it sufficiently intense now, and is its determination clear enough to prevent an “Amini solution,” which has in its favor (or against it, if one prefers) the fact that it is acceptable to the shah, that it is recommended by the foreign powers, that it aims at a Western-style parliamentary regime, and that it would undoubtedly privilege the Islamic religion? 2. Is this political will rooted deeply enough to become a permanent factor in the political life of Iran, or will it dissipate like a cloud when the sky of political reality will have finally cleared, and when we will be able to talk about programs, parties, a constitution, plans, and so forth? Politicians might say that the answers to these two questions determine much of their tactics today. With respect to this “political will,” however, there are also two questions that concern me even more deeply. One bears on Iran and its peculiar destiny. At the dawn of history, Persia invented the state and conferred its models on Islam. Its administrators staffed the caliphate. But from this same Islam, it derived a religion that gave to its people infinite resources to resist state power. In this will for an “Islamic government,” should one see a reconciliation, a contradiction, or the threshold of something new? The other question concerns this little corner of the earth whose land, both above and below the surface, has strategic importance at a global level. For the people who inhabit this land, what is the point of searching, even at the cost of their own lives, for this thing whose possibility we have forgotten since the Renaissance and the great crisis of Christianity, a political spirituality. I can already hear the French laughing, but I know that they are wrong.

Translation

Book Reviews

Book Reviews: English

Javier Sethness, “Why Did Foucault Disregard Iranian Feminists in His Support for Khomeini?” Truthout, Sept. 13, 2016 Sarah Amsler, British Journal of Sociology, Volume 57, Issue3, 2006 James Bernauer, An uncritical Foucault? Foucault and the Iranian Revolution, Philosophy & Social Criticism, Vol 32, No. 6. 2006 Jeremy Carrette, University of Kent, April 19, 2006 Babak Elahi, East-Struck: Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson’s Foucault and the Iranian Revolutionin Context, June 6, 2007 David Farber, “His Own Private Iran,” Bookforum, April-May 2005 David Frum, David Frum’s Diary, National Review Online, August 5, 2007 Lois McNay, University of Oxford, 2007 Moghadam, Valentine M., Perspectives on Politics, UNESCO, Volume 5, No. 1, March 2007 Danny Postel, Filling the Void, The Common Review, Vol. 4, No. 2 Vijay Prashad, Iranian Studies, Volume 40, No. 2, April 2007 Ahmad Sadri, Contemporary Sociology, Volume 35, No. 5 Faeghe Shirazi, Feminism and the Rule of Fundamentalism in the Islamic Republic of Iran, International Feminist Journal of Politics, Volume 9, No. 3, September 2007 Saeed Ur-Rehman, “Engaging Islam and Postmodernism,” The Friday Times, Lahore,Pakistan, January 20-26, 2006 Wesley Yang, “The Philosopher and the Ayatollah,” Boston Globe, June 12, 2005. Rafia Zakaria, The “other” Orientalism, Frontline: India’s National Magazine, Volume 22 – Issue 26, Dec. 17 – 30, 2005

.

Book Reviews: Other Languages

(Portuguese) Antonio Gonçalves Filho, “Foucault e o islà, mistura explosiva,” Estadào (Sao Paulo), March 5, 2011 (French) Azadeh Kian-Thiébaut, Abstracta Iranica, 2005 (Persian) Mehdi Khalji, BBC, Feb. 06, 2006 (Swedish) Trobjon Elensky, Dagens Nyheter, October 26, 2005